Philip Larkin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

File:Art installation Larkin with Toads 28.jpg, Sculpture of Larkin as a toad, displayed during the Larkin 25 Festival in 2010,

Homage to Philip Larkin

''The New York Review of Books'', 23 February 2006. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * James, Clive

An Affair of Sanity: Philip Larkin

''The Observer'', 25 November 1983. * * * * * Motion, Andrew (2005). "Philip Larkin" in Bayley, John and Carey, Leo (eds). ''The Power of Delight: A Lifetime in Literature: Essays, 1962–2002''. W. W. Norton & Company. . * * * Paulin, Tom (1990). "Into the Heart of Englishness," ''The Times Literary Supplement'', July 1990, reproduced in Regan, Stephen (ed.) (1997). ''Philip Larkin''. Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 160–177. * * * * * * *

Mr Larkin's Awkward Day

,

The Philip Larkin Society

Retrieved 13 November 2009. * * , a long interview with Philip Larkin.

Channel 4 television. Retrieved 13 November 2009.

The Philip Larkin Centre for Poetry and Creative Writing

University of Hull. Retrieved 13 November 2009. * . * Brown, Mark (2008)

"Photographer's papers reveal image-conscious Larkin"

''The Guardian'', 7 May 2008. * Fletcher, Christopher (2008)

"Revealingly yours, Philip Larkin"

''The Sunday Times'', 11 May 2008.

"Unknown Philip Larkin poem found in shoebox"

''The Guardian'', 6 December 2010.

Bloomfield/Larkin Papers

at the

Poetical Notebook of Philip Larkin

at the British Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Larkin, Philip 1922 births 1985 deaths Academics of the University of Hull Academics of the University of Leicester Alumni of St John's College, Oxford Deaths from cancer in England Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Deaths from esophageal cancer English agnostics English librarians English male novelists Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature Formalist poets Jazz writers Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour People educated at King Henry VIII School, Coventry People from Coventry 20th-century English poets

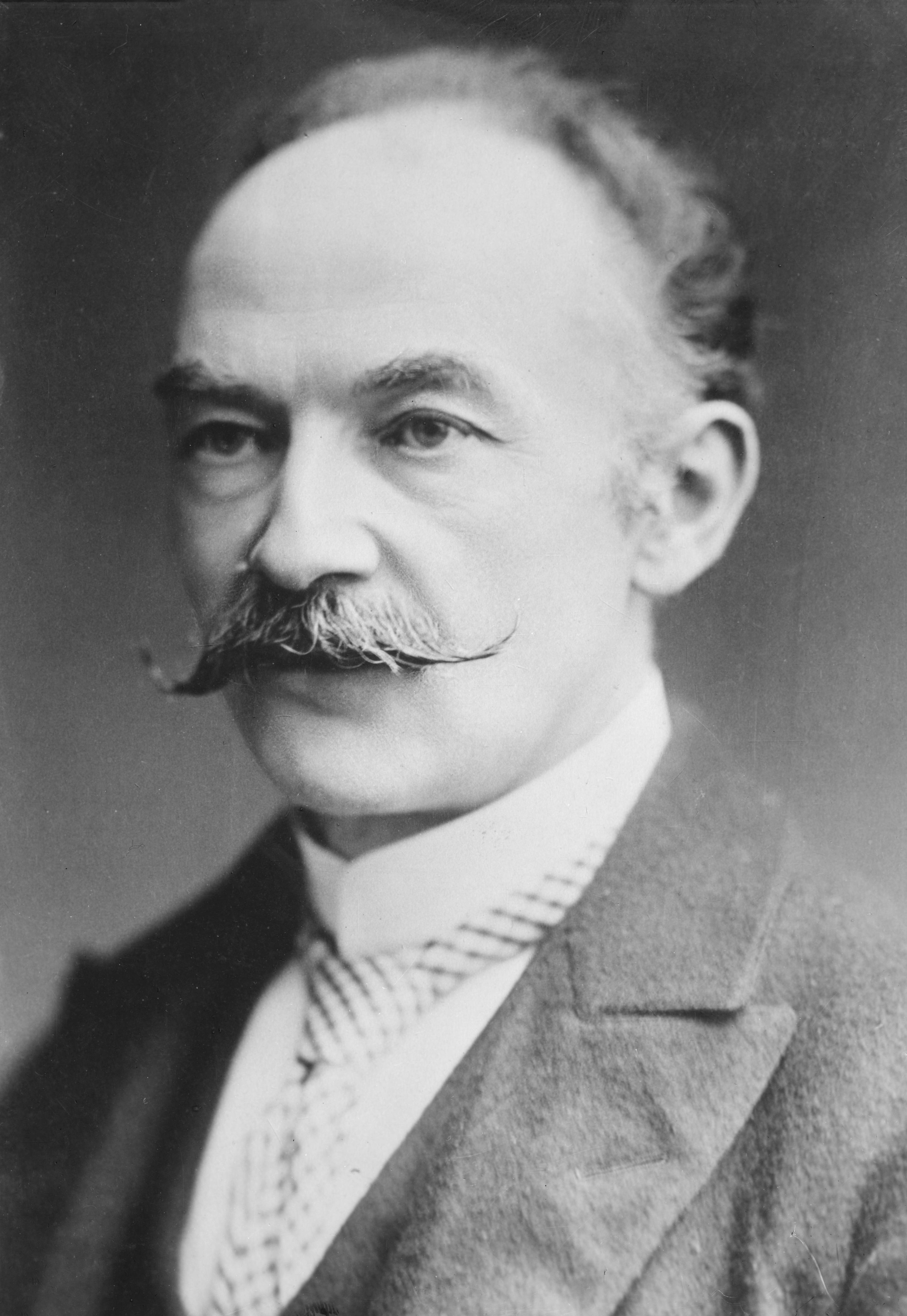

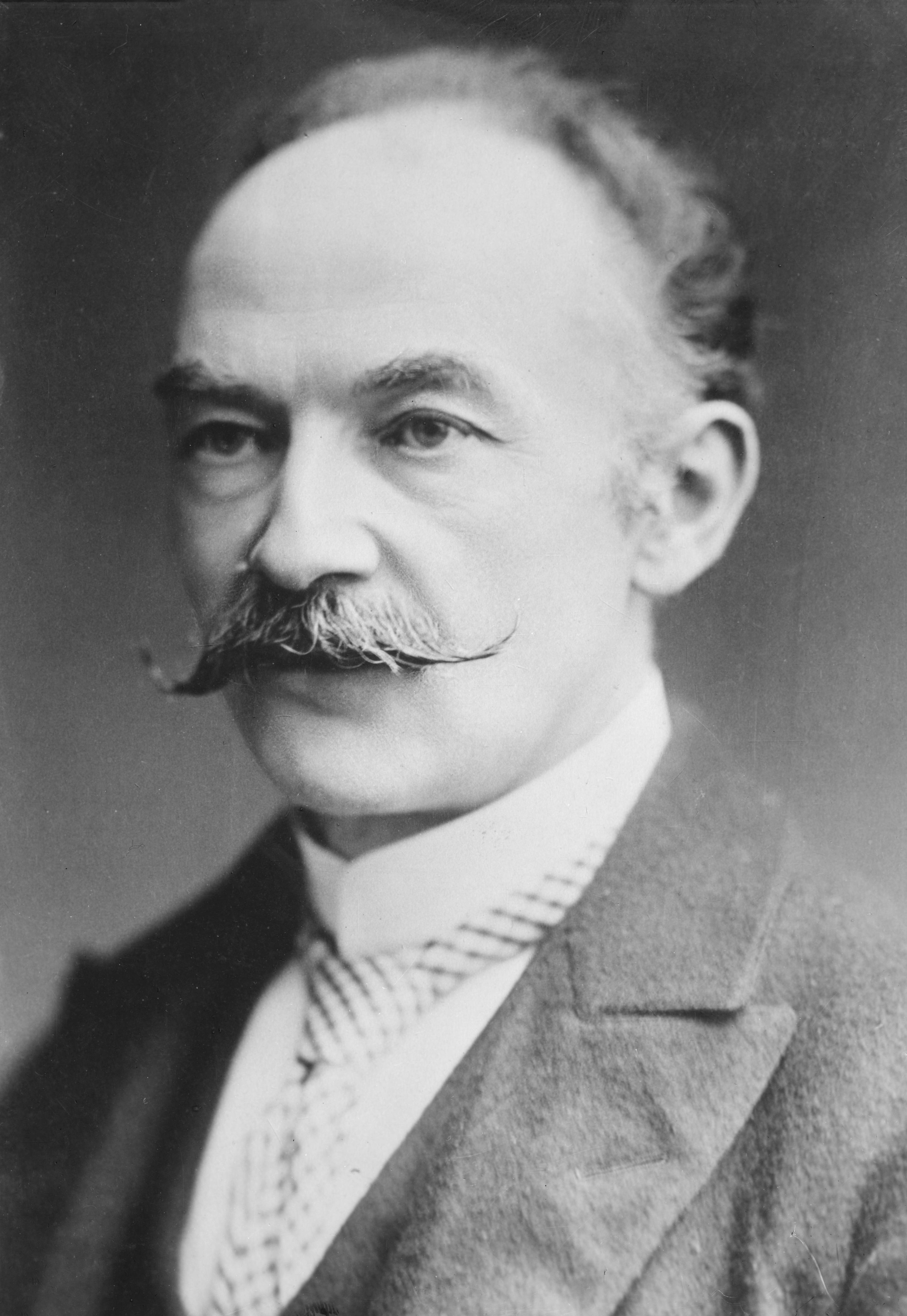

Philip Arthur Larkin (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet, novelist, and librarian. His first book of poetry, '' The North Ship'', was published in 1945, followed by two novels, '' Jill'' (1946) and '' A Girl in Winter'' (1947), and he came to prominence in 1955 with the publication of his second collection of poems, ''

Larkin's early childhood was in some respects unusual: he was educated at home until the age of eight by his mother and sister, neither friends nor relatives ever visited the family home, and he developed a stammer. Nonetheless, when he joined Coventry's King Henry VIII Junior School he fitted in immediately and made close, long-standing friendships, such as those with James "Jim" Sutton, Colin Gunner and Noel "Josh" Hughes. Although home life was relatively cold, Larkin enjoyed support from his parents. For example, his deep passion for

Larkin's early childhood was in some respects unusual: he was educated at home until the age of eight by his mother and sister, neither friends nor relatives ever visited the family home, and he developed a stammer. Nonetheless, when he joined Coventry's King Henry VIII Junior School he fitted in immediately and made close, long-standing friendships, such as those with James "Jim" Sutton, Colin Gunner and Noel "Josh" Hughes. Although home life was relatively cold, Larkin enjoyed support from his parents. For example, his deep passion for

In 1955 Larkin became University Librarian at the

In 1955 Larkin became University Librarian at the

In 1971, Larkin regained contact with his schoolfriend Colin Gunner, who had led a picturesque life. Their subsequent correspondence has gained notoriety as Larkin expressed right-wing views and used racist language. In the period from 1973 to 1974, Larkin became an Honorary Fellow of

In 1971, Larkin regained contact with his schoolfriend Colin Gunner, who had led a picturesque life. Their subsequent correspondence has gained notoriety as Larkin expressed right-wing views and used racist language. In the period from 1973 to 1974, Larkin became an Honorary Fellow of

It was during Larkin's five years in

It was during Larkin's five years in

Terence Hawkes has argued that while most of the poems in ''The North Ship'' are "metaphoric in nature, heavily indebted to Yeats's symbolist lyrics", the subsequent development of Larkin's mature style is "not ... a movement from Yeats to Hardy, but rather a surrounding of the Yeatsian moment (the metaphor) within a Hardyesque frame". In Hawkes's view, "Larkin's poetry ... revolves around two losses": the "loss of modernism", which manifests itself as "the desire to find a moment of epiphany", and "the loss of England, or rather the loss of the British Empire, which requires England to define itself in its own terms when previously it could define 'Englishness' in opposition to something else."

In 1972, Larkin wrote the oft-quoted "Going, Going", a poem which expresses a romantic

Terence Hawkes has argued that while most of the poems in ''The North Ship'' are "metaphoric in nature, heavily indebted to Yeats's symbolist lyrics", the subsequent development of Larkin's mature style is "not ... a movement from Yeats to Hardy, but rather a surrounding of the Yeatsian moment (the metaphor) within a Hardyesque frame". In Hawkes's view, "Larkin's poetry ... revolves around two losses": the "loss of modernism", which manifests itself as "the desire to find a moment of epiphany", and "the loss of England, or rather the loss of the British Empire, which requires England to define itself in its own terms when previously it could define 'Englishness' in opposition to something else."

In 1972, Larkin wrote the oft-quoted "Going, Going", a poem which expresses a romantic

When ''The Whitsun Weddings'' was released, Alvarez continued his attacks in a review in ''

When ''The Whitsun Weddings'' was released, Alvarez continued his attacks in a review in '' Chatterjee argues: "It is under the defeatist veneer of his poetry that the positive side of Larkin's vision of life is hidden". This positivity, suggests Chatterjee, is most apparent in his later works. Over the course of Larkin's poetic career: "The most notable attitudinal development lay in the zone of his view of life, which from being almost irredeemably bleak and pessimistic in ''The North Ship'', became more and more positive with the passage of time".

The view that Larkin is not a

Chatterjee argues: "It is under the defeatist veneer of his poetry that the positive side of Larkin's vision of life is hidden". This positivity, suggests Chatterjee, is most apparent in his later works. Over the course of Larkin's poetic career: "The most notable attitudinal development lay in the zone of his view of life, which from being almost irredeemably bleak and pessimistic in ''The North Ship'', became more and more positive with the passage of time".

The view that Larkin is not a

's ''Bookworm'' in 1995. Media interest in Larkin has increased in the twenty-first century. Larkin's collection ''The Whitsun Weddings'' is one of the available poetry texts in the AQA English Literature The Less Deceived

''The Less Deceived'', first published in 1955, was Philip Larkin's first mature collection of poetry, having been preceded by the derivative ''North Ship'' (1945) from The Fortune Press and a privately printed collection, a small pamphlet titl ...

'', followed by '' The Whitsun Weddings'' (1964) and '' High Windows'' (1974). He contributed to ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' as its jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

critic from 1961 to 1971, with his articles gathered in ''All What Jazz: A Record Diary 1961–71'' (1985), and edited ''The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse

''The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse'' is a poetry anthology edited by Philip Larkin. It was published in 1973 by Oxford University Press with . Larkin writes in the short preface that the selection is wide rather than deep; and a ...

'' (1973). His many honours include the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry

The Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry is awarded for a book of verse published by someone in any of the Commonwealth realms. Originally the award was open only to British subjects living in the United Kingdom, but in 1985 the scope was extended to in ...

. He was offered, but declined, the position of Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

in 1984, following the death of Sir John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture, ...

.

After graduating from Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in 1943 with a first

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

in English Language and Literature, Larkin became a librarian. It was during the thirty years he worked with distinction as university librarian at the Brynmor Jones Library at the University of Hull

The University of Hull is a public research university in Kingston upon Hull, a city in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It was founded in 1927 as University College Hull. The main university campus is located in Hull and is home to the Hull ...

that he produced the greater part of his published work. His poems are marked by what Andrew Motion calls "a very English, glum accuracy" about emotions, places, and relationships, and what Donald Davie

Donald Alfred Davie, FBA (17 July 1922 – 18 September 1995) was an English Movement poet, and literary critic. His poems in general are philosophical and abstract, but often evoke various landscapes.

Biography

Davie was born in Barnsley, ...

described as "lowered sights and diminished expectations". Eric Homberger (echoing Randall Jarrell

Randall Jarrell (May 6, 1914 – October 14, 1965) was an American poet, literary critic, children's author, essayist, and novelist. He was the 11th Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress—a position that now bears the title Poe ...

) called him "the saddest heart in the post-war supermarket"—Larkin himself said that deprivation for him was "what daffodils were for Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

". Influenced by W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, and Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

, his poems are highly structured but flexible verse forms. They were described by Jean Hartley, the ex-wife of Larkin's publisher George Hartley (the Marvell Press), as a "piquant mixture of lyricism and discontent", though anthologist Keith Tuma writes that there is more to Larkin's work than its reputation for dour pessimism suggests.Tuma 2001, p. 445.

Larkin's public persona was that of the no-nonsense, solitary Englishman who disliked fame and had no patience for the trappings of the public literary life. The posthumous publication by Anthony Thwaite in 1992 of his letters triggered controversy about his personal life and political views, described by John Banville

William John Banville (born 8 December 1945) is an Irish novelist, short story writer, adapter of dramas and screenwriter. Though he has been described as "the heir to Proust, via Nabokov", Banville himself maintains that W. B. Yeats and Henry ...

as hair-raising, but also in places hilarious.Banville 2006. Lisa Jardine

Lisa Anne Jardine (née Bronowski; 12 April 1944 – 25 October 2015) was a British historian of the early modern period.

From 1990 to 2011, she was Centenary Professor of Renaissance Studies and Director of the Centre for Editing Lives and ...

called him a "casual, habitual racist, and an easy misogynist

Misogyny () is hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women. It is a form of sexism that is used to keep women at a lower social status than men, thus maintaining the societal roles of patriarchy. Misogyny has been widely practiced f ...

", but the academic John Osborne argued in 2008 that "the worst that anyone has discovered about Larkin are some crass letters and a taste for porn softer than what passes for mainstream entertainment". Despite the controversy Larkin was chosen in a 2003 Poetry Book Society

The Poetry Book Society (PBS) was founded in 1953 by T. S. Eliot and friends, including Sir Basil Blackwell, "to propagate the art of poetry". Eric Walter White was secretary from December 1953 until 1971, and was subsequently the society's chair ...

survey, almost two decades after his death, as Britain's best-loved poet of the previous 50 years, and in 2008 ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' named him Britain's greatest post-war writer.

In 1973 a ''Coventry Evening Telegraph

The ''Coventry Telegraph'' is a local English tabloid newspaper. It was founded as ''The Midland Daily Telegraph'' in 1891 by William Isaac Iliffe, and was Coventry's first daily newspaper. Sold for half a penny, it was a four-page broadsheet ne ...

'' reviewer referred to Larkin as "the bard of Coventry", but in 2010, 25 years after his death, it was Larkin's adopted home city, Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually abbreviated to Hull, is a port city and unitary authority in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Estuary, inland from the North Sea and south-east ...

, that commemorated him with the Larkin 25

Larkin 25 was an arts festival and cultural event in Kingston upon Hull, England, organised to mark the 25th anniversary of the death of the poet and University of Hull librarian, Philip Larkin. The festival was launched at Hull Truck Theatre on ...

Festival which culminated in the unveiling of a statue of Larkin by Martin Jennings

Martin Jennings, FRBS (born 31 July 1957, in Chichester, West Sussex) a British sculptor who works in the figurative tradition, in bronze and stone. His statue of John Betjeman at St Pancras railway station was unveiled in 2007 and the statu ...

on 2 December 2010, the 25th anniversary of his death.

On 2 December 2016, the 31st anniversary of his death, a floor stone memorial for Larkin was unveiled at Poets' Corner

Poets' Corner is the name traditionally given to a section of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey in the City of Westminster, London because of the high number of poets, playwrights, and writers buried and commemorated there.

The first poe ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Life

Early life and education

Philip Larkin was born on 9 August 1922 at 2, Poultney Road,Radford, Coventry

Radford is a suburb and electoral ward of Coventry, located approximately 1.5 miles north of Coventry city centre. It is covered by the Coventry North West constituency.

Geography

Radford ward is bounded by Holbrooks, Foleshill, St Michael's, S ...

, the only son and younger child of Sydney Larkin (1884–1948) and his wife Eva Emily (1886–1977), daughter of first-class excise officer William James Day. Sydney Larkin's family originated in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, but had lived since at least the eighteenth century at Lichfield

Lichfield () is a cathedral city and civil parish in Staffordshire, England. Lichfield is situated roughly south-east of the county town of Stafford, south-east of Rugeley, north-east of Walsall, north-west of Tamworth and south-west o ...

, Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

, where they were in trade first as tailors, then also as coach-builders and shoe-makers. The Day family were of Epping, Essex, but moved to Leigh in Lancashire in 1914 where William Day took a post administering pensions and other dependent allowances.

The Larkin family lived in the district of Radford, Coventry

Radford is a suburb and electoral ward of Coventry, located approximately 1.5 miles north of Coventry city centre. It is covered by the Coventry North West constituency.

Geography

Radford ward is bounded by Holbrooks, Foleshill, St Michael's, S ...

, until Larkin was five years old, before moving to a large three-storey middle-class house complete with servants’ quarters near Coventry railway station

Coventry railway station is the main railway station serving the city of Coventry, West Midlands, England. The station is on the Birmingham loop of the West Coast Main Line (WCML); it is also located at the centre of a junction where the ...

and King Henry VIII School, in Manor Road. Having survived the bombings of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, their former house in Manor Road was demolished in the 1960s to make way for a road modernisation programme, the construction of an inner ring road. His sister Catherine, known as Kitty, was 10 years older than he was.

His father, a self-made man

"Self-made man" is a classic phrase coined on February 2, 1842 by Henry Clay in the United States Senate, to describe individuals whose success lay within the individuals themselves, not with outside conditions. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Foun ...

who had risen to be Coventry City Treasurer, was a singular individual, 'nihilistically disillusioned in middle age', who combined a love of literature with an enthusiasm for Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

, and had attended two Nuremberg rallies

The Nuremberg Rallies (officially ', meaning ''Reich Party Congress'') refer to a series of celebratory events coordinated by the Nazi Party in Germany. The first rally held took place in 1923. This rally was not particularly large or impactful; ...

during the mid-1930s. He introduced his son to the works of Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an expatriate American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Fascism, fascist collaborator in Italy during World War II. His works ...

, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

and above all D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

. His mother was a nervous and passive woman, "a kind of defective mechanism...Her ideal is 'to collapse' and to be taken care of", dominated by her husband.

Larkin's early childhood was in some respects unusual: he was educated at home until the age of eight by his mother and sister, neither friends nor relatives ever visited the family home, and he developed a stammer. Nonetheless, when he joined Coventry's King Henry VIII Junior School he fitted in immediately and made close, long-standing friendships, such as those with James "Jim" Sutton, Colin Gunner and Noel "Josh" Hughes. Although home life was relatively cold, Larkin enjoyed support from his parents. For example, his deep passion for

Larkin's early childhood was in some respects unusual: he was educated at home until the age of eight by his mother and sister, neither friends nor relatives ever visited the family home, and he developed a stammer. Nonetheless, when he joined Coventry's King Henry VIII Junior School he fitted in immediately and made close, long-standing friendships, such as those with James "Jim" Sutton, Colin Gunner and Noel "Josh" Hughes. Although home life was relatively cold, Larkin enjoyed support from his parents. For example, his deep passion for jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

was supported by the purchase of a drum kit and a saxophone

The saxophone (often referred to colloquially as the sax) is a type of single-reed woodwind instrument with a conical body, usually made of brass. As with all single-reed instruments, sound is produced when a reed on a mouthpiece vibrates to pr ...

, supplemented by a subscription to ''DownBeat

' (styled in all caps) is an American music magazine devoted to "jazz, blues and beyond", the last word indicating its expansion beyond the jazz realm which it covered exclusively in previous years. The publication was established in 1934 in Chi ...

''. From the junior school he progressed to King Henry VIII Senior School. He fared quite poorly when he sat his School Certificate

The School Certificate was a qualification issued by the Board of Studies, New South Wales, typically at the end of Year 10. The successful completion of the School Certificate was a requirement for completion of the Higher School Certificate. T ...

exam at the age of 16. Despite his results, he was allowed to stay on at school; two years later he earned distinctions in English and History, and passed the entrance exams for St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its founder, Sir Thomas White, intended to pro ...

, to read English.

Larkin began at Oxford University in October 1940, a year after the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The old upper-class traditions of university life had, at least for the time being, faded, and most of the male students were studying for highly truncated degrees. Due to his poor eyesight, Larkin failed his military medical examination and was able to study for the usual three years. Through his tutorial partner, Norman Iles, he met Kingsley Amis

Sir Kingsley William Amis (16 April 1922 – 22 October 1995) was an English novelist, poet, critic, and teacher. He wrote more than 20 novels, six volumes of poetry, a memoir, short stories, radio and television scripts, and works of social an ...

, who encouraged his taste for ridicule and irreverence and who remained a close friend throughout Larkin's life. Amis, Larkin and other university friends formed a group they dubbed "The Seven", meeting to discuss each other's poetry, listen to jazz, and drink enthusiastically. During this time he had his first real social interaction with the opposite sex, but made no romantic headway. In 1943 he sat his finals

Final, Finals or The Final may refer to:

*Final (competition), the last or championship round of a sporting competition, match, game, or other contest which decides a winner for an event

** Another term for playoffs, describing a sequence of cont ...

, and, having dedicated much of his time to his own writing, was greatly surprised at being awarded a first-class honours degree

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

.

Early career and relationships

In 1943 Larkin was appointed librarian of the public library inWellington, Shropshire

Wellington is a market town in Telford and Wrekin, Shropshire, England. It is situated 4 miles (6 km) northwest of central Telford and 12 miles (19 km) east of Shrewsbury. The summit of The Wrekin lies 3 miles southwest of the town.

The ...

. It was while working there that in early 1944 he met his first girlfriend, Ruth Bowman, an academically ambitious 16-year-old schoolgirl. In 1945, Ruth went to continue her studies at King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

; during one of his visits their friendship developed into a sexual relationship. By June 1946, Larkin was halfway through qualifying for membership of the Library Association

The Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, since 2017 branded CILIP: The library and information association (pronounced ), is a professional body for librarians, information specialists and knowledge management, knowle ...

and was appointed assistant librarian at University College, Leicester. It was visiting Larkin in Leicester and witnessing the university's Senior Common Room

A common room is a group into which students and the academic body are organised in some universities in the United Kingdom and Ireland—particularly collegiate universities such as Oxford and Cambridge, as well as the University of Bristol ...

that gave Kingsley Amis the inspiration to write ''Lucky Jim

''Lucky Jim'' is a novel by Kingsley Amis, first published in 1954 by Victor Gollancz. It was Amis's first novel and won the 1955 Somerset Maugham Award for fiction. The novel follows the exploits of the eponymous James (Jim) Dixon, a reluctant ...

'' (1954), the novel that made Amis famous and to whose long gestation Larkin contributed considerably.Motion 1993, p. 238. Six weeks after his father's death from cancer in March 1948, Larkin proposed to Ruth, and that summer the couple spent their annual holiday touring Hardy country.Bradford 2005, p. 70.

In June 1950 Larkin was appointed sub-librarian at The Queen's University of Belfast

, mottoeng = For so much, what shall we give back?

, top_free_label =

, top_free =

, top_free_label1 =

, top_free1 =

, top_free_label2 =

, top_free2 =

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public research university

, parent = ...

, a post he took up that September. Before his departure he and Ruth split up. At some stage between the appointment to the position at Queen's and the end of the engagement to Ruth, Larkin's friendship with Monica Jones, a lecturer in English at Leicester, also developed into a sexual relationship. He spent five years in Belfast, which appear to have been the most contented of his life. While his relationship with Jones developed, he also had "the most satisfyingly erotic xperienceof his life" with Patsy Strang, who at the time was in an open marriage

Open marriage is a form of non-monogamy in which the partners of a dyadic marriage agree that each may engage in extramarital sexual relationships, without this being regarded by them as infidelity, and consider or establish an open relatio ...

with one of his colleagues. At one stage she offered to leave her husband to marry Larkin. From 1951 onwards Larkin holidayed with Jones in various locations around the British Isles. While in Belfast he also had a significant though sexually undeveloped friendship with Winifred Arnott, the subject of "Lines on a Young Lady's Photograph Album", which came to an end when she married in 1954. This was the period in which he gave Kingsley Amis extensive advice on the writing of ''Lucky Jim''. Amis repaid the debt by dedicating the finished book to Larkin.

In 1955 Larkin became University Librarian at the

In 1955 Larkin became University Librarian at the University of Hull

The University of Hull is a public research university in Kingston upon Hull, a city in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England. It was founded in 1927 as University College Hull. The main university campus is located in Hull and is home to the Hull ...

, a post he held until his death. Professor R. L. Brett, who was chairman of the library committee that appointed him and a friend, wrote, "At first I was impressed with the time he spent in his office, arriving early and leaving late. It was only later that I realised that his office was also his study where he spent hours on his private writing as well as the work of the library. Then he would return home and on a good many evenings start writing again." For his first year he lodged in bedsits. In 1956, at the age of 34, he rented a self-contained flat on the top-floor of 32 Pearson Park, a three-storey red-brick house overlooking the park, previously the American Consulate. This, it seems, was the vantage point later commemorated in the poem '' High Windows.'' Of the city itself Larkin commented: "I never thought about Hull until I was here. Having got here, it suits me in many ways. It is a little on the edge of things, I think even its natives would say that. I rather like being on the edge of things. One doesn't really go anywhere by design, you know, you put in for jobs and move about, you know, I've lived in other places." In the post-war years, Hull University underwent significant expansion, as was typical of British universities during that period. When Larkin took up his appointment there, the plans for a new university library were already far advanced. He made a great effort in just a few months to familiarize himself with them before they were placed before the University Grants Committee; he suggested a number of emendations, some major and structural, all of which were adopted. It was built in two stages, and in 1967 it was named the Brynmor Jones Library after Sir Brynmor Jones, the university's vice-chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and former Commonwealth n ...

.

One of Larkin's colleagues at Hull said he became a great figure in post-war British librarianship. Ten years after the new library's completion, Larkin computerized records for the entire library stock, making it the first library in Europe to install a Geac computer system, an automated online circulation system. Richard Goodman wrote that Larkin excelled as an administrator, committee man and arbitrator. "He treated his staff decently, and he motivated them", Goodman said. "He did this with a combination of efficiency, high standards, humour and compassion." He rejected the Net Book Agreement. From 1957 until his death, Larkin's secretary was Betty Mackereth. All access to him by his colleagues was through her, and she came to know as much about Larkin's compartmentalized life as anyone. During his 30 years there, the library's stock sextupled, and the budget expanded from £4,500 to £448,500, in real terms a twelvefold increase.

Later life

In February 1961 Larkin's friendship with his colleague Maeve Brennan became romantic, despite her strong Roman Catholic beliefs. In early 1963 Brennan persuaded him to go with her to a dance for university staff, despite his preference for smaller gatherings. This seems to have been a pivotal moment in their relationship, and he memorialised it in his longest (and unfinished) poem "The Dance". Around this time, also at her prompting, Larkin learnt to drive and bought a car – his first, aSinger Gazelle

The Singer Gazelle name has been applied to two generations of motor cars from the British manufacturer Singer. It was positioned between the basic Hillman range and the more sporting Sunbeam versions.

Gazelle I and II

The Gazelle was the ...

. Meanwhile, Monica Jones, whose parents had died in 1959, bought a holiday cottage in Haydon Bridge

Haydon Bridge is a village in Northumberland, England, with a population of about 2000, the civil parish Haydon being measured at 2,184 in the Census 2011. Its most distinctive features are the two bridges crossing the River Tyne, River South T ...

, near Hexham

Hexham ( ) is a market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in Northumberland, England, on the south bank of the River Tyne, formed by the confluence of the North Tyne and the South Tyne at Warden, Northumberland, Warden nearby, and ...

, which she and Larkin visited regularly. His poem "Show Saturday" is a description of the 1973 Bellingham show in the North Tyne valley.

In 1964, following the publication of '' The Whitsun Weddings'', Larkin was the subject of an edition of the arts programme ''Monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

'', directed by Patrick Garland

Patrick Ewart Garland (10 April 1935 – 19 April 2013) was a British director, writer and actor.

Career

Garland was educated at St Mary's College, Southampton, and St Edmund Hall, Oxford where he studied English and was Literary Editor of Isi ...

. The programme, which shows him being interviewed by fellow poet John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture, ...

in a series of locations in and around Hull, allowed Larkin to play a significant part in the creation of his own public persona; one he would prefer his readers to imagine.

In 1968, Larkin was offered the OBE, which he declined. Later in life he accepted the offer of being made a Companion of Honour.

Larkin's role in the creation of Hull University's new Brynmor Jones Library had been important and demanding. Soon after the completion of the second and larger phase of construction in 1969, he was able to redirect his energies. In October 1970, he started to work on compiling a new anthology, ''The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse

''The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse'' is a poetry anthology edited by Philip Larkin. It was published in 1973 by Oxford University Press with . Larkin writes in the short preface that the selection is wide rather than deep; and a ...

'' (1973). He was awarded a Visiting Fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford

All Souls College (official name: College of the Souls of All the Faithful Departed) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full members of t ...

, for two academic terms, allowing him to consult Oxford's Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

, a copyright library

A national library is a library established by a government as a country's preeminent repository of information. Unlike public libraries, these rarely allow citizens to borrow books. Often, they include numerous rare, valuable, or significant wo ...

. While he was in Oxford he passed responsibility for the Library to his deputy, Brenda Moon. Larkin was a major contributor to the re-evaluation of the poetry of Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

, which, in comparison to his novels, had been overlooked; in Larkin's "idiosyncratic" and "controversial" anthology,Motion 1993, p. 431. Hardy was the poet most generously represented. There were twenty-seven poems by Hardy, compared with only nine by T. S. Eliot (however, Eliot is most famous for long poems); the other poets most extensively represented were W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

, W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

and Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

. Larkin included six of his own poems—the same number as for Rupert Brooke

Rupert Chawner Brooke (3 August 1887 – 23 April 1915)The date of Brooke's death and burial under the Julian calendar that applied in Greece at the time was 10 April. The Julian calendar was 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar. was an En ...

. In the process of compiling the volume he had been disappointed not to find more and better poems as evidence that the clamour over the Modernists

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

had stifled the voices of traditionalists. The most favourable responses to the anthology were those of Auden and John Betjeman, while the most hostile was that of Donald Davie

Donald Alfred Davie, FBA (17 July 1922 – 18 September 1995) was an English Movement poet, and literary critic. His poems in general are philosophical and abstract, but often evoke various landscapes.

Biography

Davie was born in Barnsley, ...

, who accused Larkin of "positive cynicism" and of encouraging "the perverse triumph of philistinism, the cult of the amateur ... ndthe weakest kind of Englishry". After an initial period of anxiety about the anthology's reception, Larkin enjoyed the clamour.

In 1971, Larkin regained contact with his schoolfriend Colin Gunner, who had led a picturesque life. Their subsequent correspondence has gained notoriety as Larkin expressed right-wing views and used racist language. In the period from 1973 to 1974, Larkin became an Honorary Fellow of

In 1971, Larkin regained contact with his schoolfriend Colin Gunner, who had led a picturesque life. Their subsequent correspondence has gained notoriety as Larkin expressed right-wing views and used racist language. In the period from 1973 to 1974, Larkin became an Honorary Fellow of St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its founder, Sir Thomas White, intended to pro ...

, and was awarded honorary degree

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hono ...

s by Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

, St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

and Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

universities. In January 1974, Hull University informed Larkin that they were going to dispose of the building on Pearson Park in which he lived. Shortly afterwards he bought a detached two-storey 1950s house in Newland Park which was described by his university colleague John Kenyon as "an entirely middle-class backwater". Larkin, who moved into the house in June, thought the four-bedroom property "utterly undistinguished" and reflected, "I can't say it's the kind of dwelling that is eloquent of the nobility of the human spirit".

Shortly after splitting up with Maeve Brennan in August 1973, Larkin attended W. H. Auden's memorial service at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniqu ...

, with Monica Jones as his official partner. In March 1975, the relationship with Brennan restarted, and three weeks after this he initiated a secret affair with Betty Mackereth, who served as his secretary for 28 years, writing the long-undiscovered poem "We met at the end of the party" for her. Despite the logistical difficulties of having three relationships simultaneously, the situation continued until March 1978. From then on he and Jones were a monogamous couple.

In 1976, Larkin was the guest of Roy Plomley

Francis Roy Plomley, ( ; 20 January 1914 – 28 May 1985) was an English radio broadcaster, producer, playwright and novelist. He is best remembered for devising the BBC Radio series ''Desert Island Discs'', which he hosted from its inception i ...

on BBC's ''Desert Island Discs

''Desert Island Discs'' is a radio programme broadcast on BBC Radio 4. It was first broadcast on the BBC Forces Programme on 29 January 1942.

Each week a guest, called a " castaway" during the programme, is asked to choose eight recordings (usu ...

''. His choice of music included "Dallas Blues

"Dallas Blues", written by Hart Wand, is an early blues song, first published in 1912. It has been called the first true blues tune ever published. However, two other 12-bar blues had been published earlier: Anthony Maggio's "I Got the Blues" in ...

" by Louis Armstrong

Louis Daniel Armstrong (August 4, 1901 – July 6, 1971), nicknamed "Satchmo", "Satch", and "Pops", was an American trumpeter and vocalist. He was among the most influential figures in jazz. His career spanned five decades and several era ...

, ''Spem in alium

''Spem in alium'' (Latin for "Hope in any other") is a 40-part Renaissance motet by Thomas Tallis, composed in c. 1570 for eight choirs of five voices each. It is considered by some critics to be the greatest piece of English early music. H. B. ...

'' by Thomas Tallis

Thomas Tallis (23 November 1585; also Tallys or Talles) was an English composer of High Renaissance music. His compositions are primarily vocal, and he occupies a primary place in anthologies of English choral music. Tallis is considered one o ...

and the Symphony No. 1 in A flat major by Edward Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

. His favourite piece was "I'm Down in the Dumps" by Bessie Smith

Bessie Smith (April 15, 1894 – September 26, 1937) was an American blues singer widely renowned during the Jazz Age. Nicknamed the " Empress of the Blues", she was the most popular female blues singer of the 1930s. Inducted into the Rock and ...

.

In December 2010, as part of the commemorations of the 25th anniversary of Larkin's death, the BBC broadcast a programme entitled ''Philip Larkin and the Third Woman'' focusing on his affair with Mackereth in which she spoke for the first time about their relationship. It included a reading of a newly discovered secret poem, ''Dear Jake'', and revealed that Mackereth was one of the inspirations for his writings.

Final years and death

Larkin turned sixty in 1982. This was marked most significantly by a collection of essays entitled '' Larkin at Sixty'', edited by Anthony Thwaite and published byFaber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

.Thwaite 1982. There were also two television programmes: an episode of ''The South Bank Show

''The South Bank Show'' is a British television arts magazine series originally produced by London Weekend Television and broadcast on ITV between 1978 and 2010. A new version of the series began 27 May 2012 on Sky Arts. Conceived, written, ...

'' presented by Melvyn Bragg

Melvyn Bragg, Baron Bragg, (born 6 October 1939), is an English broadcaster, author and parliamentarian. He is best known for his work with ITV as editor and presenter of ''The South Bank Show'' (1978–2010), and for the BBC Radio 4 documenta ...

in which Larkin made off-camera contributions, and a half-hour special on the BBC that was devised and presented by the Labour Shadow Cabinet Minister Roy Hattersley

Roy Sydney George Hattersley, Baron Hattersley, (born 28 December 1932) is a British Labour Party politician, author and journalist from Sheffield. He was MP for Birmingham Sparkbrook for over 32 years from 1964 to 1997, and served as Depu ...

.

In 1983, Jones was hospitalised with shingles

Shingles, also known as zoster or herpes zoster, is a viral disease characterized by a painful skin rash with blisters in a localized area. Typically the rash occurs in a single, wide mark either on the left or right side of the body or face. ...

, a skin rash. The severity of her symptoms, including its effects on her eyes, distressed Larkin. As her health declined, regular care became necessary: within a month she moved into his Newland Park home and remained there for the rest of her life.

At the memorial service for John Betjeman, who died in July 1984, Larkin was asked if he would accept the post of Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

. He declined, not least because he felt he had long since ceased to be a writer of poetry in a meaningful sense. The following year, Larkin began to suffer from oesophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer is cancer arising from the esophagus—the food pipe that runs between the throat and the stomach. Symptoms often include difficulty in swallowing and weight loss. Other symptoms may include pain when swallowing, a hoarse voice ...

. On 11 June 1985, he underwent surgery, but his cancer was found to have spread and was inoperable. On 28 November, he collapsed and was readmitted to hospital. He died four days later, on 2 December 1985, at the age of 63, and was buried at Cottingham municipal cemetery near Hull.

Larkin had asked on his deathbed that his diaries be destroyed. The request was granted by Jones, the main beneficiary of his will, and Betty Mackereth; the latter shredded the unread diaries page by page, then had them burned. His will was found to be contradictory regarding his other private papers and unpublished work; legal advice left the issue to the discretion of his literary executors, who decided the material should not be destroyed. When she died on 15 February 2001, Jones, in turn, left £1 million to St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in London and is the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London. It is on Ludgate Hill at the highest point of the City of London and is a Grad ...

, Hexham Abbey

Hexham Abbey is a Grade I listed place of Christian worship dedicated to St Andrew, in the town of Hexham, Northumberland, in the North East of England. Originally built in AD 674, the Abbey was built up during the 12th century into its curre ...

and Durham Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Christ, Blessed Mary the Virgin and St Cuthbert of Durham, commonly known as Durham Cathedral and home of the Shrine of St Cuthbert, is a cathedral in the city of Durham, County Durham, England. It is the seat of t ...

. Larkin is commemorated with a green plaque on The Avenues, Kingston upon Hull

The Avenues is an area of high status Victorian housing located in the north-west of Kingston upon Hull, England. It is formed by four main tree-lined straight avenues running west off the north-north-east/south-south-west running ''Princes Ave ...

.

Creative output

Juvenilia and early works

From his mid-teens, Larkin "wrote ceaselessly", producing both poetry, initially modelled on Eliot and W. H. Auden, and fiction: he wrote five full-length novels, each of which he destroyed shortly after their completion. While he was at Oxford University, his first published poem, "Ultimatum", appeared in '' The Listener''. He developed a pseudonymous alter ego in this period for his prose: Brunette Coleman. Under this name he wrote two novellas, ''Trouble at Willow Gables'' and ''Michaelmas Term at St Brides'' (2002), as well as a supposed autobiography and an equally fictitious creative manifesto called "What we are writing for". Richard Bradford has written that these curious works show "three registers: cautious indifference, archly overwritten symbolism with a hint of Lawrence and prose that appears to disclose its writer's involuntary feelings of sexual excitement". After these works, Larkin began to write his first published novel '' Jill'' (1946). This was published by Reginald A. Caton, a publisher of barely legal pornography, who also issued serious fiction as a cover for his core activities. Around the time that ''Jill'' was being prepared for publication, Caton inquired of Larkin if he also wrote poetry. This resulted in the publication, three months before ''Jill'', of '' The North Ship'' (1945), a collection of poems written between 1942 and 1944 which showed the increasing influence ofYeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

. Immediately after completing ''Jill'', Larkin started work on the novel ''A Girl in Winter'' (1947), completing it in 1945. This was published by Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

and was well received, ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' calling it "an exquisite performance and nearly faultless". Subsequently, he made at least three concerted attempts at writing a third novel, but none developed beyond a solid start.

Mature works

It was during Larkin's five years in

It was during Larkin's five years in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

that he reached maturity as a poet. The bulk of his next published collection of poems, ''The Less Deceived

''The Less Deceived'', first published in 1955, was Philip Larkin's first mature collection of poetry, having been preceded by the derivative ''North Ship'' (1945) from The Fortune Press and a privately printed collection, a small pamphlet titl ...

'' (1955), was written there, though eight of the twenty-nine poems included were from the late 1940s. This period also saw Larkin make his final attempts at writing prose fiction, and he gave extensive help to Kingsley Amis with ''Lucky Jim

''Lucky Jim'' is a novel by Kingsley Amis, first published in 1954 by Victor Gollancz. It was Amis's first novel and won the 1955 Somerset Maugham Award for fiction. The novel follows the exploits of the eponymous James (Jim) Dixon, a reluctant ...

'', which was Amis's first published novel. In October 1954 an article in ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'' made the first use of the title The Movement

The Movement may refer to:

Politics

* The Movement (Iceland), a political party in Iceland

* The Movement (Israel), a political party in Israel, led by Tzipi Livni

* Civil rights movement, the African-American political movement

* The Movemen ...

to describe the dominant trend in British post-war literature. Poems by Larkin were included in a 1953 PEN

A pen is a common writing instrument that applies ink to a surface, usually paper, for writing or drawing. Early pens such as reed pens, quill pens, dip pens and ruling pens held a small amount of ink on a nib or in a small void or cavity wh ...

Anthology that also featured poems by Amis and Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

, and Larkin was seen to be a part of this grouping. In 1951, Larkin compiled a collection called ''XX Poems'' which he had privately printed in a run of just 100 copies. Many of the poems in it subsequently appeared in his next published volume.

In November 1955, ''The Less Deceived'', was published by the Marvell Press, an independent company in Hessle

Hessle () is a town, civil parish and electoral ward in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England, west of Kingston upon Hull city centre. Geographically it is part of a larger urban area consisting of the city of Kingston upon Hull, the town of ...

near Hull (dated October). At first the volume attracted little attention, but in December it was included in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' list of ''Books of the Year''.Motion 1993, p. 269. From this point, the book's reputation spread and sales blossomed throughout 1956 and 1957. During his first five years in Hull, the pressures of work slowed Larkin's output to an average of just two-and-a-half poems a year, but this period saw the writing of some of his best-known poems, such as " An Arundel Tomb", " The Whitsun Weddings" and "Here".

In 1963, Faber and Faber reissued ''Jill'', with the addition of a long introduction by Larkin that included much information about his time at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and his friendship with Kingsley Amis. This acted as a prelude to the publication the following year of '' The Whitsun Weddings'', the volume which cemented his reputation; a Fellowship of the Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820, by George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV, to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, th ...

was granted to Larkin almost immediately. In the years that followed, Larkin wrote several of his most best-known poems, followed in the 1970s by a series of longer and more sober poems, including "The Building" and "The Old Fools". All of these appeared in Larkin's final collection, '' High Windows'', which was published in June 1974. Its more direct use of language meant that it did not meet with uniform praise; nonetheless it sold over twenty thousand copies in its first year alone. For some critics it represents a falling-off from his previous two books, yet it contains a number of his much-loved pieces, including " This Be The Verse" and "The Explosion", as well as the title poem. "Annus Mirabilis" (Year of Wonder), also from that volume, contains the frequently quoted observation that sexual intercourse began in 1963, which the narrator claims was "rather late for me". Bradford, prompted by comments in Maeve Brennan's memoir, suggests that the poem commemorates Larkin's relationship with Brennan moving from the romantic to the sexual.

Later in 1974 he started work on his final major published poem, "Aubade". It was completed in 1977 and published in 23 December issue of ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication i ...

''. After "Aubade" Larkin wrote only one poem that has attracted close critical attention, the posthumously published and intensely personal "Love Again".

Poetic style

Larkin's poetry has been characterized as combining "an ordinary, colloquial style", "clarity", a "quiet, reflective tone", "ironic understatement" and a "direct" engagement with "commonplace experiences", while Jean Hartley summed his style up as a "piquant mixture of lyricism and discontent". Larkin's earliest work showed the influence of Eliot, Auden and Yeats, and the development of his mature poetic identity in the early 1950s coincided with the growing influence on him ofThomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Word ...

. The "mature" Larkin style, first evident in ''The Less Deceived'', is "that of the detached, sometimes lugubrious, sometimes tender observer", who, in Hartley's phrase, looks at "ordinary people doing ordinary things". He disparaged poems that relied on "shared classical and literary allusions – what he called ''the myth-kitty'', and the poems are never cluttered with elaborate imagery." Larkin's mature poetic persona is notable for its "plainness and scepticism". Other recurrent features of his mature work are sudden openings and "highly-structured but flexible verse forms".

Terence Hawkes has argued that while most of the poems in ''The North Ship'' are "metaphoric in nature, heavily indebted to Yeats's symbolist lyrics", the subsequent development of Larkin's mature style is "not ... a movement from Yeats to Hardy, but rather a surrounding of the Yeatsian moment (the metaphor) within a Hardyesque frame". In Hawkes's view, "Larkin's poetry ... revolves around two losses": the "loss of modernism", which manifests itself as "the desire to find a moment of epiphany", and "the loss of England, or rather the loss of the British Empire, which requires England to define itself in its own terms when previously it could define 'Englishness' in opposition to something else."

In 1972, Larkin wrote the oft-quoted "Going, Going", a poem which expresses a romantic

Terence Hawkes has argued that while most of the poems in ''The North Ship'' are "metaphoric in nature, heavily indebted to Yeats's symbolist lyrics", the subsequent development of Larkin's mature style is "not ... a movement from Yeats to Hardy, but rather a surrounding of the Yeatsian moment (the metaphor) within a Hardyesque frame". In Hawkes's view, "Larkin's poetry ... revolves around two losses": the "loss of modernism", which manifests itself as "the desire to find a moment of epiphany", and "the loss of England, or rather the loss of the British Empire, which requires England to define itself in its own terms when previously it could define 'Englishness' in opposition to something else."

In 1972, Larkin wrote the oft-quoted "Going, Going", a poem which expresses a romantic fatalism

Fatalism is a family of related philosophical doctrines that stress the subjugation of all events or actions to fate or destiny, and is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are tho ...

in its view of England that was typical of his later years. In it he prophesies a complete destruction of the countryside, and expresses an idealised sense of national togetherness and identity: "And that will be England gone ... it will linger on in galleries; but all that remains for us will be concrete and tyres". The poem ends with the blunt statement, "I just think it will happen, soon."

Larkin's style is bound up with his recurring themes and subjects, which include death and fatalism, as in his final major poem "Aubade". Poet Andrew Motion observes of Larkin's poems: "their rage or contempt is always checked by the ... energy of their language and the satisfactions of their articulate formal control". Motion contrasts two aspects of his poetic personality—on the one hand, an enthusiasm for "symbolist moments" and "freely imaginative narratives", and on the other a "remorseless factuality" and "crudity of language". Motion defines this as a "life-enhancing struggle between opposites", and concludes that his poetry is typically "ambivalent": "His three mature collections have developed attitudes and styles of ... imaginative daring: in their prolonged debates with despair, they testify to wide sympathies, contain passages of frequently transcendent beauty, and demonstrate a poetic inclusiveness which is of immense consequence for his literary heirs."

Prose non-fiction

Larkin was a critic ofmodernism

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

in contemporary art and literature. His scepticism is at its most nuanced and illuminating in ''Required Writing'', a collection of his book reviews and essays, and at its most inflamed and polemical in his introduction to his collected jazz reviews, ''All What Jazz'', drawn from the 126 record-review columns he wrote for ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'' between 1961 and 1971, which contains an attack on modern jazz that widens into a wholesale critique of modernism in the arts. Larkin (not unwillingly) acquired a reputation as an enemy of modernism, but recent critical assessments of Larkin's writings have identified them as possessing some modernist characteristics.

Legacy

Reception history

When first published in 1945, ''The North Ship'' received just one review, in the ''Coventry Evening Telegraph

The ''Coventry Telegraph'' is a local English tabloid newspaper. It was founded as ''The Midland Daily Telegraph'' in 1891 by William Isaac Iliffe, and was Coventry's first daily newspaper. Sold for half a penny, it was a four-page broadsheet ne ...

'', which concluded "Mr Larkin has an inner vision that must be sought for with care. His recondite imagery is couched in phrases that make up in a kind of wistful hinted beauty what they lack in lucidity. Mr Larkin's readers must at present be confined to a small circle. Perhaps his work will gain wider appeal as his genius becomes more mature?" A few years later, though, the poet and critic Charles Madge

Charles Henry Madge (10 October 1912 – 17 January 1996) was an English poet, journalist and sociologist, now most remembered as a founder of Mass-Observation. Philip Bounds, ''Orwell and Marxism: the political and cultural thinking of George ...

came across the book and wrote to Larkin with his compliments. When the collection was reissued in 1966, it was presented as a work of juvenilia, and the reviews were gentle and respectful; the most forthright praise came from Elizabeth Jennings in ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'': "few will question the intrinsic value of ''The North Ship'' or the importance of its being reprinted now. It is good to know that Larkin could write so well when still so young."

''The Less Deceived'' was first noticed by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', who included it in its ''List of Books of 1955''. In its wake many other reviews followed; "most of them concentrated ... on the book's emotional impact and its sophisticated, witty language." ''The Spectator'' felt the collection was "in the running for the best published in this country since the war"; G. S. Fraser

George Sutherland Fraser (8 November 1915 – 3 January 1980) was a Scotland, Scottish poet, literary critic and academic.

Biography

Fraser was born in Glasgow, Scotland, later moving with his family to Aberdeen. He attended the University of ...

, referring to Larkin's perceived association with The Movement

The Movement may refer to:

Politics

* The Movement (Iceland), a political party in Iceland

* The Movement (Israel), a political party in Israel, led by Tzipi Livni

* Civil rights movement, the African-American political movement

* The Movemen ...

felt that Larkin exemplified "everything that is good in this 'new movement' and none of its faults".Bradford 2005, p. 144. ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication i ...

'' called him "a poet of quite exceptional importance", and in June 1956, the ''Times Educational Supplement

''Tes'', formerly known as the ''Times Educational Supplement'', is a weekly UK publication aimed at education professionals. It was first published in 1910 as a pull-out supplement in ''The Times'' newspaper. Such was its popularity that in 19 ...

'' was fulsome: "As native as a Whitstable oyster, as sharp an expression of contemporary thought and experience as anything written in our time, as immediate in its appeal as the lyric poetry of an earlier day, it may well be regarded by posterity as a poetic monument that marks the triumph over the formless mystifications of the last twenty years. With Larkin poetry is on its way back to the middlebrow public." Reviewing the book in America, the poet Robert Lowell

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (; March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet. He was born into a Boston Brahmin family that could trace its origins back to the ''Mayflower''. His family, past and present, were important subjects i ...

wrote: "No post-war poetry has so caught the moment, and caught it without straining after its ephemera. It's a hesitant, groping mumble, resolutely experienced, resolutely perfect in its artistic methods."Motion 1993, p. 328.

In time, there was a counter-reaction: David Wright wrote in ''Encounter

Encounter or Encounters may refer to:

Film

*''Encounter'', a 1997 Indian film by Nimmala Shankar

* ''Encounter'' (2013 film), a Bengali film

* ''Encounter'' (2018 film), an American sci-fi film

* ''Encounter'' (2021 film), a British sci-fi film

* ...

'' that ''The Less Deceived'' suffered from the "palsy of playing safe". In April 1957, Charles Tomlinson

Alfred Charles Tomlinson, CBE (8 January 1927 – 22 August 2015) was an English poet, translator, academic, and illustrator.

He was born in Penkhull, and grew up in Basford, Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire.

Life

After attending Longton High Sc ...

wrote a piece for the journal ''Essays in Criticism'', "The Middlebrow Muse", attacking The Movement's poets for their "middle-cum-lowbrowism", "suburban mental ratio" and "parochialism"—Larkin had a "tenderly nursed sense of defeat". In 1962, A. Alvarez

Alfred Alvarez (5 August 1929 – 23 September 2019) was an English poet, novelist, essayist and critic who published under the name A. Alvarez and Al Alvarez.

Background

Alfred Alvarez was born in London, to an Ashkenazic Jewish mother and a ...

, the compiler of an anthology entitled '' The New Poetry'', accused Larkin of "gentility, neo-Georgian pastoralism, and a failure to deal with the violent extremes of contemporary life".

The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'', complaining of the "drab circumspection" of Larkin's "commonplace" subject-matter. Praise outweighed criticism; John Betjeman felt Larkin had "closed the gap between poetry and the public which the experiments and obscurity of the last fifty years have done so much to widen." In ''The New York Review of Books

''The New York Review of Books'' (or ''NYREV'' or ''NYRB'') is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of i ...

'', Christopher Ricks

Sir Christopher Bruce Ricks (born 18 September 1933) is a British literary critic and scholar. He is the William M. and Sara B. Warren Professor of the Humanities at Boston University (US), co-director of the Editorial Institute at Boston Un ...

wrote of the "refinement of self-consciousness, usually flawless in its execution" and Larkin's summoning up of "the world of all of us, the place where, in the end, we find our happiness, or not at all." He felt Larkin to be "the best poet England now has."

In his biography, Richard Bradford writes that the reviews for ''High Windows'' showed "genuine admiration" but notes that they typically encountered problems describing "the individual genius at work" in poems such as "Annus Mirabilis", "The Explosion" and "The Building" while also explaining why each were "so radically different" from one another. Robert Nye in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' overcame this problem "by treating the differences as ineffective masks for a consistently nasty presence".

In '' Larkin at Sixty'', amongst the portraits by friends and colleagues such as Kingsley Amis, Noel Hughes and Charles Monteith and dedicatory poems by John Betjeman, Peter Porter and Gavin Ewart

Gavin Buchanan Ewart FRSL (4 February 1916 – 23 October 1995) was a British poet who contributed to Geoffrey Grigson's ''New Verse'' at the age of seventeen.

Life

Ewart was born in London and educated at Wellington College, before entering ...

, the various strands of Larkin's output were analysed by critics and fellow poets: Andrew Motion, Christopher Ricks and Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

looked at the poems, Alan Brownjohn

Alan Charles Brownjohn (born 28 July 1931) is an English poet and novelist. He has also worked as a teacher, lecturer, critic and broadcaster.

Life and work

Alan Brownjohn was born in London and educated at Merton College, Oxford. He taught in ...

wrote on the novels, and Donald Mitchell and Clive James

Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.Thom Gunn

Thomson William "Thom" Gunn (29 August 1929 – 25 April 2004) was an English poet who was praised for his early verses in England, where he was associated with The Movement, and his later poetry in America, even after moving towards a looser, ...

or Donald Davie

Donald Alfred Davie, FBA (17 July 1922 – 18 September 1995) was an English Movement poet, and literary critic. His poems in general are philosophical and abstract, but often evoke various landscapes.

Biography

Davie was born in Barnsley, ...

". But since the turn of the century, Larkin's standing has increased. "Philip Larkin is an excellent example of the plain style in modern times", writes Tijana Stojkovic. Robert Sheppard asserts: "It is by general consent that the work of Philip Larkin is taken to be exemplary". "Larkin is the most widely celebrated and arguably the finest poet of the Movement", states Keith Tuma, and his poetry is "more various than its reputation for dour pessimism and anecdotes of a disappointed middle class suggests".